Android inter-process communication (IPC)

TL;DR; if you want to get a very good understanding into how Android inter-process communication works, check out the following outstanding video about the Android Binder framework internals. It is long, but I really recommend it!

Inter Process Communication (IPC) has been a part of Android since 1.0, and yet most of us take it for granted. Intents, content providers, and system service managers hide the IPC infrastructure provided by Binder, but without it, the Android OS and our apps would simply fall apart. Binder/IPC is the glue that holds it all together. It enables Android’s memory management, security sandboxing, efficient threading, and countless other features on the Android platform.

What are bound services

A bound service is the server in a client-server interface. It allows other components to bind to the service, send requests, receive responses, and perform interprocess communication (IPC). Multiple clients can connect to a service simultaneously. A bound service typically lives only while it serves another application component and does not run in the background indefinitely, but an indefinitely running service can also be implemented in a way that clients can bind to it. For more information on service lifecycle, please refer to the official Android documentation about Managing the lifecycle of a bound service.

How to build a bound service

There are 3 different ways implement a bound service:

- Extending the Binder class - this approach can be used when the client and the service live in the same codebase and run in the same process. When clients connect to the service, they can simply cast the received IBinder to the service implementation class, because both Service and Client are in the same codebase. Then they can directly call the service methods in a safe way. The client calls and service reponses run in the application main thread by default, but can be extended to run in a background thread with a bit of extra work.

- Using a Messenger - we will go into much detail about this particular technique in this article. For now, it’s just important to mention it supports communication between different processes and also across different code bases with the help of a bit of shared code. The threading model depends on the implementation, but typically there is a single background thread with message queue, where all clients send commands.

- Using AIDL - This approach is the most abstract and most flexible of all. It does not normally require any shared code except for the service interface declared in the so called Android Interface Definition Language (AIDL) files. Each connected client sends calls to the service from a different thread, so it also requires thread-safe implementation on the service side.

Bound services with Messenger

In this article we will implement a bound service, using the Messenger approach. We’ll also extract part of the needed code as common shared code, we will call contract. This will allow us to use the Messenger approach even between apps that do not shared a common code base. You can find here the official documentation for implementing Messenger bound service.

Which components do we need

- Service - A Service is an application component representing either an application’s desire to perform a longer-running operation while not interacting with the user or to supply functionality for other applications to use. In our case we need to extend this class in order to implement a bound service.

- ServiceConnection - this interface is used by a client in order to establish connection with a bound service. It gets callbacks from the OS, when the client connects to a service or when the connection is lost.

- Messenger - This class represents a reference to a Handler, which others can use in order to send messages to it. This allows for the implementation of message-based communication across processes, by creating a Messenger pointing to a Handler in one process, and handing that Messenger to another process. In our case, when connected to a bound service, the clients receive a Messenger initialized by that service. They can use it to send IPC calls to the bound service. If they want to receive responses back from the bound service, then they need to initialize their own Messenger, and pass it via the replyTo field of the messages they send to the bound service. This way, when the bound service receives a Message containing a replyTo Messenger, it could extract this Messenger and send the response messages through it.

- Handler - A Handler allows to send and process Message objects associated with a thread’s MessageQueue. In our case, the service needs to initialize a Handler, wrap it into a Messenger and provide this Messenger to connected clients so that they can send messages. The incoming messages can be processed in the handleMessage method of the Handler.

- Message - Defines a message containing a description and arbitrary data object that can be sent to a Handler. In our case, both client calls to the bound service and service responses will be wrapped into instances of the Message class and passed through the corresponding Messenger.

- Intent - An intent is an abstract description of an operation to be performed. In our case it is used when clients want to bind to a remote service. It contains the necessary information, so that the OS can locate the application and component, where the implementation of the bound service is done. On the service side, when client binds, the incoming Intent can be used to identify the connecting client.

- Bundle - A mapping from String keys to various Parcelable values. In our case, Bundles are used to define the properties of the bind Intent constructed by the client. In addition, all data in Message sent back and forth between client and service is a Bundle.

Defining the common contract

When Messengers are used for bound service communication, there are no explicit calls to particular service methods, instead Messages have to include enough payload and metadata to uniquely define the operation which the service should perform.

In addition, Messages are very generic objects, therefore the service and the client have to share a common contract for defining the available commands, flags, payload formatting, and common Parcelable data classes. This contract has to be shared between the client and service, which means a shared library in case they are located in different apps.

The following code snippets wrap the common contract into a convenient to use class.

class MessengerContract {

class InvalidPayloadException(message: String) : RuntimeException(message)

companion object {

private const val SERVICE_PACKAGE_NAME = "com.luboganev.testground"

private const val SERVICE_CLASS_NAME = "$SERVICE_PACKAGE_NAME.demos.ipcMessenger.service.MessengerService"

val serviceBindIntent: Intent

get() {

return Intent()

.setComponent(

ComponentName(SERVICE_PACKAGE_NAME, SERVICE_CLASS_NAME)

)

}

const val WHAT_SAY_HELLO = 1

const val WHAT_ADD_TWO_NUMBERS = 2

const val WHAT_ADD_TWO_NUMBERS_RESULT = 3

}

}We start by defining common constants, such as Message types, properties related to establishing the initial service connection and common exception. Next up, we define a class related to each Request-Response communication channel between the service and the client.

...

class SayHello {

companion object {

private val PAYLOAD_KEY_MESSAGE = "message"

fun buildRequestMessage(messageText: String) : Message {

val message = Message.obtain(null, WHAT_SAY_HELLO, 0, 0)

message.data = wrapRequestMessagePayload(messageText)

return message

}

private fun wrapRequestMessagePayload(messageText: String): Bundle {

val payload = Bundle()

payload.putString(PAYLOAD_KEY_MESSAGE, messageText)

return payload

}

fun parseRequestMessagePayload(payload: Bundle?): String {

if (payload != null && payload.containsKey(PAYLOAD_KEY_MESSAGE)) {

return payload.getString(MessengerContract.SayHello.PAYLOAD_KEY_MESSAGE)

} else {

throw InvalidPayloadException("Payload of SayHello request is missing")

}

}

}

}

...This class defines constants needed to encode the payload of messages as well convenience methods for building and parsing the Messages sent between clients and the service. In case a service response is required, we can extend this structure a bit by adding a replyTo Messenger, like the following example:

...

class AddTwoIntegers {

companion object {

private val PAYLOAD_KEY_NUMBERS_CONTAINER = "numbers_container"

private val PAYLOAD_KEY_NUMBERS_ADDITION_RESULT = "numbers_addition_result"

fun buildRequestMessage(twoIntegers: TwoIntegersContainer, replyTo: Messenger) : Message {

val message = Message.obtain(null, WHAT_ADD_TWO_NUMBERS, 0, 0)

message.data = wrapRequestMessagePayload(twoIntegers)

message.replyTo = replyTo

return message

}

private fun wrapRequestMessagePayload(twoIntegers: TwoIntegersContainer): Bundle {

val payload = Bundle()

payload.putParcelable(PAYLOAD_KEY_NUMBERS_CONTAINER, twoIntegers)

return payload

}

}

...For the full implementation of the contract and all related helper methods and classes, please refer to the source code of the sample app on GitHub and more specifically the module containing the shared code

Building the service part

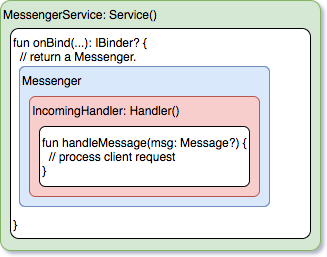

Building the service part is pretty simple and requires just a few components.

And here’s the corresponding code snippet to the diagram.

class MessengerService : Service() {

class IncomingHandler(val applicationContext: Context) : Handler() {

override fun handleMessage(msg: Message?) {

// handle messages

}

}

val messenger by lazy { Messenger(IncomingHandler(applicationContext)) }

override fun onBind(intent: Intent): IBinder? {

return messenger.binder

}

}- We declare a Handler and implement the message handling in its handleMessage() method

- We extend the Service class and override it’s onBind method.

- We wrap the declared Handler into a Messenger implementation and return it from the onBind method. Messenger class implements IBinder, so wo don’t have to do any casting.

The following code snippet demonstrates how different types of client messages are handled in the Handler.

...

override fun handleMessage(msg: Message?) {

when(msg?.what) {

MessengerContract.WHAT_SAY_HELLO -> {

val incomingMessage = MessengerContract.SayHello.parseRequestMessagePayload(msg.data)

// show message to user

}

MessengerContract.WHAT_ADD_TWO_NUMBERS -> {

try {

val twoIntegersContainer = MessengerContract.AddTwoIntegers.parseRequestMessagePayload(msg.data)

// calculate result and wrap it into a result

val resultMessage = MessengerContract.AddTwoIntegers.buildResponseMessage(

twoIntegersContainer.first + twoIntegersContainer.second)

// use the replyTo to send back result to client messenger

msg.replyTo.send(resultMessage)

} catch (e: MessengerContract.InvalidPayloadException) {

// show invalid payload error to user

}

}

else -> {

// show unknown message type error to user

}

}

}

...Building the client part

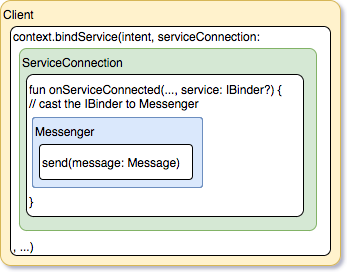

Building the client is also very easy an includes just a few components.

And here’s the corresponding code snippet to the diagram.

...

private fun bindToService() {

if (!boundToService) {

bindService(MessengerContract.serviceBindIntent, messengerServiceConnection, BIND_AUTO_CREATE)

}

}

private fun unbindFromService() {

if (boundToService) {

unbindService(messengerServiceConnection)

boundToService = false

serviceCallsMessenger = null

}

}

private var serviceCallsMessenger: Messenger? = null

private val messengerServiceConnection = object : ServiceConnection {

override fun onServiceDisconnected(name: ComponentName?) {

boundToService = false

serviceCallsMessenger = null

}

override fun onServiceConnected(name: ComponentName?, service: IBinder?) {

serviceCallsMessenger = Messenger(service)

boundToService = true

}

}

...- We implement a ServiceConnection interface, which receives callbacks when connection is established or lost.

- We call context.bindService() method and pass the ServiceConnection in it.

- We wrap the received IBinder into a Messenger, which basically represents the service Messenger we have defined in the Service implementation above.

- We call the send() method of the messenger to send messages to the service.

Time to play - try out the different options in the companion app

I have included a demo in the blog’s companion app where you can test the Messenger IPC, including two types of remote service calls:

- Fire-and-forget - Call, which sends a String message to the service and expects no response

- Request-Response - A call to the service sending two integers, which expects a response with the result of their addition. In addition, the integers are packed into a custom data class, in order to demonstrate the ability to send Parcelable payload through the Messenger API.

You can find the source code on GitHub