The drama we have avoided

I guess every developer has at some point tried to come up with some clean architectural model. Most of the time, however, this happens in a late stage of the project, thus incorporating any particular architecture more often than not requires major refactoring and complete rebuild of many components. This is a pretty high cost, which the product management often does not want to pay, because it will probably not bring any direct benefit or improvement to the product’s users and the project’s stakeholders. Therefore, it never happens and the problems keep deepening until somebody burns out, screams loudly or becomes increasingly unhappy with his job and eventually quits. In order to avoid such dramatic events, our team has looked for some clean architecture from the very start of our project.

Uncle Bob’s clean architecture

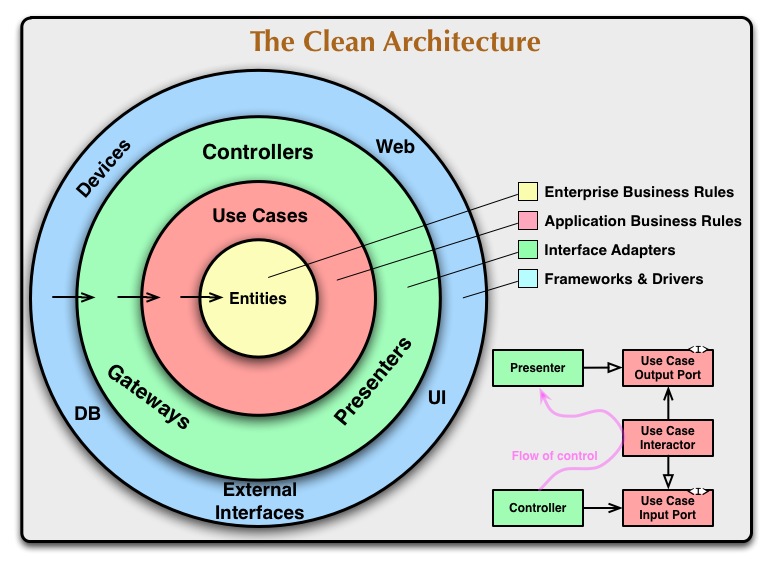

We went a long way back to fundaments of software engineering theory and we have discovered Uncle Bob’s Clean architecture.

The original blog post describing in detail this architecture can be found here: Link. Although it dates back to 2012, it describes a fundamental approach, which could be used for building flexible and testable software in general. It does not matter if you are building a website, web application, desktop application or mobile app. The basic principles, guaranteeing better separation of concerns and better modularization of your software project, hold all the aforementioned domains. The most important aspect of this architecture is the so called Dependency rule.

Nothing in an inner circle can know anything at all about something in an outer circle. In particular, the name of something declared in an outer circle must not be mentioned by the code in the an inner circle. That includes, functions, classes. variables, or any other named software entity.

In addition to this rule, all connections and communication between components from neighboring circles should be abstractly implemented, e.g. by using simple POJOs and Interfaces when building for Android in Java, or using Protocols and standard classes, when building in Objective-C and Swift in iOS. Such an architecture is extremely flexible and testable. Practically, the implementation of every single component from a particular circle could be completely changed or mocked, without having to make any changes in other parts of the code.

This all looks pretty nice, but is also very vague and abstract. You might ask, how would one go on with implementing it in a mobile app? Luckily some smart people have already done the hard work and have come up with a version of the clean architecture matches very well the domain of iOS mobile apps. It is called VIPER architecture for iOS.

V.I.P.E.R architecture for iOS

The original blog post describing in detail this architecture can be found here: Link. Further high quality read is the objc.io article on this topic which can be found here: Link.

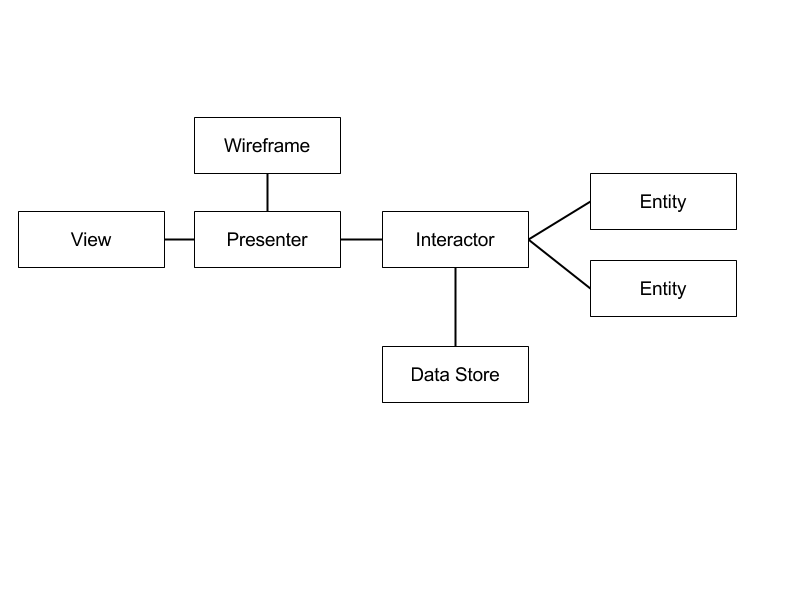

VIPER stands for Views, Interactors, Presenters, Entities and Routing. The combination of all these components lives inside the so called Module. The main motivation behind this architecture is to provide a solution to a problem in iOS known as Massive View Controllers. The traditional MVC architecture used to develop iOS application simply does not provide enough modularity and separation of concerns. The View and the Model parts remain more or less clean, but all complexity ends up in the ViewControllers, which have to manage simply too much stuff. Over 1000 lines of code is not that uncommon for a relatively feature-rich ViewController. VIPER tries to follow the single responsibility principle and splits all these responsibilities among a couple of classes in order to provide a better modularity and separation of concerns.

Looking in more detail into VIPER and the sample project on the website reveals slightly different naming and some extra components.

I will not go into too much detail about the particular implementation or discuss every single component, because it is already superbly presented in the articles described above. The one thing I would like to put more focus on is the communication taking place between the Presenter and the Interactor. The Interactor works with the Entities and never passed them to the Presenter. Instead the so called DisplayData objects are being built from the Entities. These objects contain only the data requred by the Presenter to be shown in the View. Think of a typical List/Detail application. You probably have models with a lot of fields, but only a subset of these fields is presented in the list. In that case, the ListDisplayData and DetailDisplayData would both be created from the same model, but will contain different number of fields and may even contain some transformed versions of the original fields.

There are a couple of things one has to keep an eye on, when using the VIPER architecture in iOS. The first thing is that one has to instantiate all the components with their dependencies and do all the wiring between them in a module. This can feel like writing a lot of the same boilerplate code, every time when a new module is created, but there is no way around it. We have tried to automate a little bit this process by writing custom code snippets and code generation scripts, but many times the results prove to be too general for specific module we are currently building.

Another tricky thing to look for comes as a result of the manual wiring mentioned above - cyclic strong references. Since some of the components need their cyclic references in order to work, e.g. Presenter<->Interactor, one can really quickly produce serious memory leaks if not being careful, which references can be strong and which should be weak. This task becomes more complicated the more components and modules there are in the application. Additional hidden memory leaks might happen when using cool language features such as Swift’s closures, so be extra careful when calling Presenter methods from a closure located inside the Interactor.

Finally, this strict separation of concerns sometimes leads to having a really simple Presenters, which just redirect some data flow from the View to the Interactors. This happens when the architecture is applied to a relatively simple screens, which do not have a lot of stuff for the Presenter to do.

Apart from these “problems”, we as a team are really happy with our decision to give this architecture a try. It has not only proven to make sure we code better, but also allowed us to be faster in our development. I believe two main factors are the simpler and shorter components we have developed and the common architectural language, that we have acquired. The former ensures that we can understand what happens in a particular component faster and make code reviews faster due to its and simplicity. The latter helps us to talk the same language, when we plan how to implement new features and ensures no crazy styles of programming is going on, which is can be a problem when more than a couple of different developers work on the same project.

One does not simply use VIPER in Android

Once we got pretty comfortable with the VIPER architecture in iOS, we wanted to have something similar when building our Android app. However, there are some significant differences in the way the SDKs work in iOS and Android. The following paragraphs describe some of these differences, which make it tricky to directly apply the VIPER architecture to Android.

Android has Activities, which are more or less the equivalent of the iOS’s ViewControllers. A big difference is that one cannot instantiate these objects. One can just ask the Framework to start an Activity and then can override its lifecycle methods in order to do any necessary work. So when implementing VIPER modules, one cannot do the whole wiring in a Wireframe class when the Activity is instantiated. Instead all the initial VIPER module wiring has to take place when an Activity is initialized and started by the Framework itself. The Android SDK also provides Fragments, which can indeed we can be instantiated by us, but there is so much magic related to Fragment creation, which the framework does automatically, that you can never be sure that you have full control over your Fragments. Therefore, I don’t consider using Fragments as the VIPER Views and explicitly instantiating them in a Wireframe as a stable solution. Fighting against the framework is always a bad idea.

Another specific thing in Android are the configuration changes, which normally destroy the whole UI and recreate it. That includes Activities, Fragments and Views. That can prove to be catastrophic, because the whole VIPER Module will be garbage collected and recreated again. So one has to make sure that the state of Module components is saved in some way. In addition, one has to be careful with long-living objects and operations keeping references to the Module components, because they might cause big memory leaks. A typical example is a network request operation, which has a strong reference to the Module’s Interactor as its callback. Since the Interactor holds reference to the Presenter and it hold reference to the View, which holds reference to all UI stuff, this might result in a big memory leak. So one needs to take care of cleaning up such references when a whole Module is being destroyed and recreated. An extremely useful tool for hunting for such memory leaks was recently open-sourced by the guys from Square Inc. and is called Leak Canary and you should be using it even if you are not planning doing any VIPER stuff. Check it out here: Link

Android app architecture is a hot topic

Fortunately, app architecture is a really hot topic lately, and there are more than enough articles and blog posts describing different approaches for building different architectures in Android - classical concepts such as MVP, MVVM, MVC and some pretty radical new approaches like the Square way with Mortar and Flow. The next part of this series will present briefly some of the sources I have found and used while makeing a concept on how to migrate the VIPER architecture to Android. Stay tuned for part 3.