Although one could write a detailed description of the concepts and ideas behind an architecture, I believe that the easiest way to understand it is to see an example. Therefore, I have built a simple demo application, which is built with the VIPER architecture in mind. The following sections describe the application and some specifics related to Android.

Where is the code?

The demo app is called Car brands and is an open-source project hosted at GitHub. You can find the repository here: Repository Link

(Update 11.05.2016) If you are cloning the repository, please be advised that this particular post refers to an older revision of the code and not the HEAD from the master branch. It is tagged with the tag v1.1. You can find it here: Repository Link TAG v1.1

If you do not feel like building the app yourself or cloning the repository, you can alternatively download the source and a ready built debug apk file from the release section of the project at GitHub. Please find it here: Release Link

Overview of the app architecture with Dagger

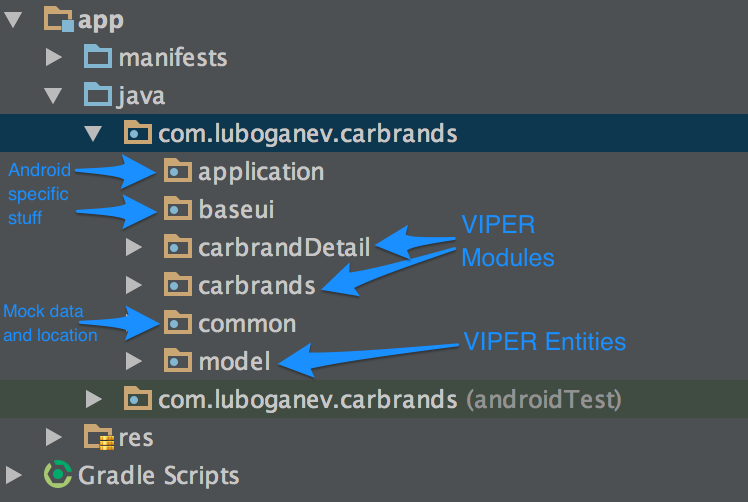

The application’s UI has an extremely simple List/Detail screens structure. The following screenshot shows how the application packages look like in Android Studio.

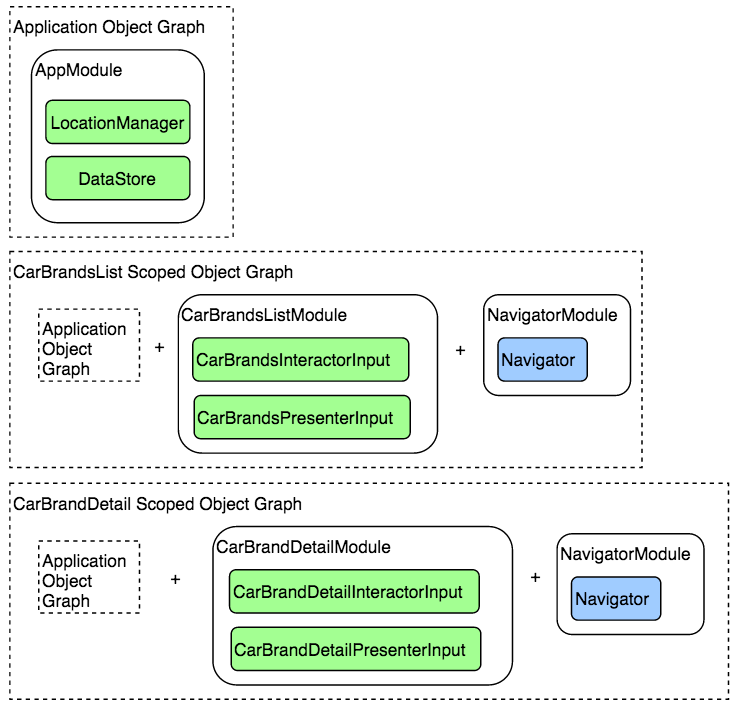

It has two simple Activities, which represent the two screens of the application. Thus, there are two VIPER modules - carbrands, which contains components related the list, and carbrandDetail, which contains components related to the detail. All instantiating of VIPER components such as Interactors and Presenters and their dependencies is done inside the Dagger’s Module classes. There are in total four Dagger Modules in the project - AppModule, NavigatorModule, CarBrandsListModule and CarBrandDetailModule. Those four modules are used for building up the Dagger’s object graph and all scoped object graphs, but more on this in the following paragraphs. Let’s first start with a diagram, showing the Modules and the different objects graph they form.

The root Dagger Object Graph contains the main AppModule. It provides instances of the mock implementations of a data store and location manager to all classes which might need them. The NavigatorModule provides instance of the Navigator class, which contains logic for navigating from the ListActivity to the DetailActivity. The CarBrandsListModule provides instances of the Presenter and Interactor related to the list VIPER module. It and the Navigator module are being added to the Application’s object graph in order to create a scoped graph related only to the list screen of the app. Similarly, the CarBrandDetailModule provides instances of the Presenter and Interactor related to the detail VIPER module, and is added to the Application object graph together with the NavigatorModule in order to create a scoped object graph related only to the detail screen of the app.

So why using scoped graphs at all and make our life harder? Since the UI of the application has a shorter lifecycle in comparison with the application process, we do not need to persist in memory all possible dependencies related to the list and detail VIPER modules all the time. Therefore, we use the scoped graph Dagger functionality and we build an extended version of the Object Graph, containing the main Application Object Graph and the Modules related only to the Activity being shown. After the Activity goes away, its scoped object graph with all its instances is garbage collected, without affecting the instances of dependencies living in the Application object graph.

In the current implementation almost all dependency injection is performed through constructor injection. This all happens in the provider methods of the Dagger Module classes, when instantiating the concrete implementations of the Interactors and Presenters. The only object we cannot create are the Android Activities. Therefore, we need to use field injection there, after these objects have been instantiated by the Android framework. In order to encapsulate the functionality related to creating scoped graphs and field-injecting an instantiated Activity, the demo app includes a BaseDaggerActivity abstract class, which performs these commons tasks. There is also a custom implementation of the Application class, which contains the logic for creating the initial root Application Dagger Object Graph. The following code snippets depict what are possibly the two most important classes in the demo application.

public abstract class BaseDaggerActivity extends AppCompatActivity {

private @Nullable ObjectGraph mActivityGraph;

@Override

protected void onCreate(@Nullable Bundle savedInstanceState) {

super.onCreate(savedInstanceState);

List<Object> modules = getActivityModules();

if(modules != null && modules.size() > 0) {

mActivityGraph = CarBrandsApplication.get(this).createScopedGraph(modules.toArray());

}

if(shouldInjectSelf()) {

if (mActivityGraph != null) {

mActivityGraph.inject(this);

} else {

CarBrandsApplication.get(this).inject(this);

}

onInjected(savedInstanceState);

}

}

@Override

protected void onDestroy() {

super.onDestroy();

mActivityGraph = null;

}

/**

* This method should return a list of modules to be added as a scoped object graph

* to the Application's object graph. If it does not provide any modules,

* the current Activity does not generate its own scoped object graph and uses the

* Application's object graph instead.

*/

protected @Nullable List<Object> getActivityModules() { return null; }

/**

* This method returns whether the current Activity itself

* should be injected with dependencies

*/

protected boolean shouldInjectSelf() { return false; }

/**

* A helper method used to inject objects. It uses the Activity's the scoped object

* graph if one exists. In case the Activity does not have its own scoped object graph,

* the Application's object graph is used for the injection.

*

* @param object

* The object to be injected with dependencies

*/

protected void inject(@NonNull Object object) {

if(mActivityGraph == null) {

CarBrandsApplication.get(this).inject(object);

} else {

mActivityGraph.inject(object);

}

}

/**

* This method gets called once the Activity has been injected.

* It is a hook you can use if you want to do something as early as

* in the onCreate() but still need the injected dependencies

*

* @param savedInstanceState

* The reference to the savedInstanceState from the onCreate method.

*/

protected void onInjected(@Nullable Bundle savedInstanceState) {}

}public class CarBrandsApplication extends Application {

private ObjectGraph objectGraph;

@Override

public void onCreate() {

super.onCreate();

objectGraph = ObjectGraph.create(new AppModule(this));

}

/**

* A helper method, which creates a scoped Dagger object graph, by adding the input

* modules to the root Application object graph.

*

* @param modules

* The additional modules which should be included in the scoped object graph.

* @return

* An instance of the created scoped object graph

*/

public ObjectGraph createScopedGraph(Object... modules) {

return objectGraph.plus(modules);

}

/**

* A helper method which injects objects with their dependencies from the

* the Application's object graph

*

* @param object

* The object to be injected

*/

public void inject(@NonNull Object object) {

objectGraph.inject(object);

}

/**

* A helper method which gets a reference to the Application from an input Activity instance

*/

public static CarBrandsApplication get(@NonNull Activity activity) {

return (CarBrandsApplication) activity.getApplication();

}So when the application is launched, the root object graph is created from the AppModule. Shortly after that, the CarBrandsListActivity is being launched. Since it extends the BaseDaggerActivity, it inherits the functionality implemented inside the onCreate() method. There are two important tasks, which the overridden implementation of this method performs:

- Create an Activity scoped object graph - this depends on the return value of the method getActivityModules(). If the Activity has any Dagger Modules which it wants to extend the ApplicationObject graph with, it can provide them by overriding this method. In case there are no modules to be added, then no scoped graph is created.

- Inject the Activity itself with dependencies - Whether the Activity should attempt to inject itself or not depends on the return value of the method shouldInjectSelf(). While injecting itself, the Activity will try to use the local scoped object graph first. However, if it is not available, it will inject from the Application’s object graph instead.

For even more documentation and comments inside these two classes, please refer to the code of the demo app.

Building up a VIPER module and its components

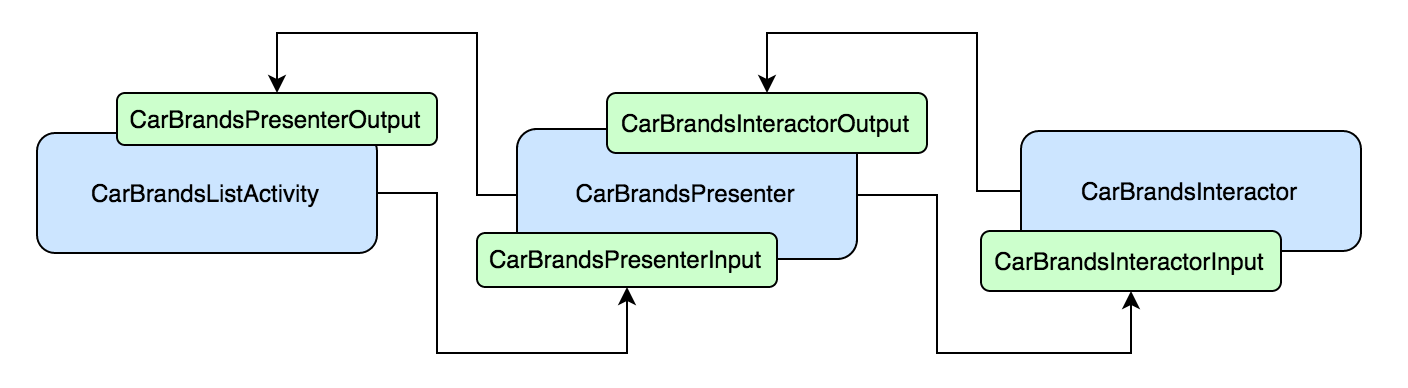

The very basic implementation of a VIPER module in this context consists of a View, a Presenter and an Interactor. To keep the implementation flexible and mockable, dependencies are defined as Java interfaces.

For example, the CarBrandsListActivity needs a reference to its presenter, i.e. the CarBrandsPresenter. But instead of reference to the concrete implementation, the CarBrandsListActivity gets injected a CarBrandsPresenterInput. Similarly, the presenter does not get injected a reference to the Activity, but instead an interface called CarBrandsPresenterOutput, implemented by the Activity. Furthermore, the communication between the presenter and the interactor goes through the methods defined inside the CarBrandsInteractorInput and CarBrandsInteractorOutput, while the concrete interactor implementation is defined in the CarBrandsInteractor class.

When a new screen is shown, i.e. an Activity is created, it requires a Presenter. What hapens is that Dagger will find a method, which provides the implementation of the Presenter in the particular Dagger Module, and inject it. In order to create the Presenter, however, an instance of the Interactor is needed as well, since the Presenter has references to both Interactor and View (the Activity). But to create an Interactor, we need to have an instance of the Presenter, since the Interactor has a reference to it. Having such a cyclic relation between two dependencies cannot be implemented with Dagger and injection. After all, that is what Dagger stands for - Directed Acyclic Graph, i.e. (DAG)ger. It does not support cyclic dependencies. So this is a problem.

There is an easy solution - we just need to make one of the injections through a setter method instead of using constructor injection. So we do not provide an instance of the presenter to the interactor through its constructor, but instead through a setter method after it has been instantiated. This is an exception to the rule, we have established, for using constructor injection for objects, which we can instantiate, but a needed one when using Dagger dependency injection and VIPER architecture together. A similar case might have been the relation between Presenter and View, but it is not the case, because we perform field injection there. In addition, the presenters get their View dependency directly from the Dagger Module itself, since it is being instantiated by the Activity in its getActivityModules(), thus this dependency is also not automatically provided by Dagger, but is provided, so to say, by design.

Saving state

The proposed architecture heavily depends on Activities, since they are responsible for creating, keeping and destroying the scoped object graphs and all dependencies living there. So what happens when a configuration change occurs? Naturally, the activity gets destroyed together with all the VIPER components from the module related to this Activity. So one still has to make sure he saves any needed state. Since every component might need to save and restore some kind of state, the provided implementation includes a common Java interface for that purpose.

/**

* This interface defines some important Activity lifecycle callbacks, which most probably

* every Presenter would care knowing about

*

* Created by Lyubomir Ganev (ganevlyu) on 27.04.2015

*/

public interface ViewLifecycleCallbacks {

/**

* Called when an activity's onResume method is invoked

*/

void onViewShow();

/**

* Called when an activity's onSaveInstanceState method is invoked

*

* @param savedInstanceState

* The bundle to use for saving state

*/

void onViewSaveState(Bundle savedInstanceState);

/**

* Called when an activity's has just been created.

*

* @param launchingIntentExtras

* This bundle contains the extras from the Activity's launching Intent. It may be null.

* @param savedInstanceState

* This bundle contains the extras of the saved instance state. It may be null;

*/

void onViewCreate(@Nullable Bundle launchingIntentExtras, @Nullable Bundle savedInstanceState);

/**

* Called when an activity's onDestroy is invoked.

*

* @param isExiting

* If the activity's onDestroy is a result of the Activity going away. If this flag is false,

* this probably means that the Activity is being destroyed due to a configuration change or

* a low memory situation and will be re-created again.

*/

void onViewDestroy(boolean isExiting);

}For example, if the Presenter wants to save and restore some state, it needs to implement this interface. In addition, the View, i.e. Activity of this Presenter, needs to call the methods defined in the interface, when it gets the according Activity callbacks. In case the Interactor needs to save and restore state, it and the Presenter both have to implement the methods from the interface. Then the Activity has to call the Presenter, which has call the Interactor, since the Interactor and the View have no direct connection with one another.

Long-running atomic operations

Sometimes saving simple state is not enough. There are long running operations, which occur in another thread in the background. In addition, some of them have to be atomic, e.g. user sends a payment request to server. You probably want to make sure, that only a single payment is sent even when configuration changes occur while request is running, but still be able to retrieve the results of such operation once it is done. So how to do it?

Let’s start by where should the according component making the request be placed in this architecture. Since most if not all of the scoped graphs are tightly coupled with a UI, one cannot put a component with a potentially longer lifecycle than the UI lifecycle inside one of these. This might firstly cause memory leaks, and secondly cannot guarantee that the result of the long-running operation will be shown at all in the UI, since it might no longer be shown. Therefore, such long-lifecycle components should be living in the Application’s object graph, where they live as long as the application’s process itself. There, they can safely keep state and cache results, without being destroyed every time the user rotates the device.

The second part of the solution is how the Interactor of a particular VIPER Module communicates with these components. Well, pretty simple - it gets them as dependecies and attaches and detaches from them when it gets created or destroyed. It also can register to listen to any callbacks from them while attached. Finally, it can also check any cached state or last operation result on attach they might have, in case the operation got complete while the Interactor was destroyed and recreated and was not listening.

Summary

The presented architecture is still a work in progress and there will certainly be situations when it will present some challenges. That being said, our team has successfully implemented and released a feature-rich Android application with much more complicated UI by following this architecture. We have not identified any huge drawback so far, but you can be assured that if that happens, I will write about it. For now, I hope I have managed to inspire you to try out developing for Android in the spirit of the clean architecture. Cheers.